Hey! This is totally random and absolutely not connected to any recent tyrannical police updates, but did you know you can find me on Mastodon?! It’s true: https://mastodon.sdf.org/@taskbaarchitect

Hope to see you there!

Hey! This is totally random and absolutely not connected to any recent tyrannical police updates, but did you know you can find me on Mastodon?! It’s true: https://mastodon.sdf.org/@taskbaarchitect

Hope to see you there!

Look, it’s a portfolio update! Well, given that there’s another couple of books on the way it seemed high time to bring the list of my recent projects up to speed.

Yes, Heart of Fire is my second Sea of Thieves novel – though given that I’ve been working on the game itself pretty much full-time since its Anniversary update in 2019, it’s not like I’m returning to that universe after an extended absence or anything. It’s once again set before the events of the game and likewise once again follows another two crews – separated not by the passage of time, but by finding themselves on different sides of the same conflict. It’ll be out soon, and I’m probably going to break Twitter by refreshing my feed too much. Much excite!

What with that, my recent work on a vinyl boxset, the upcoming release of The Art of Battletoads and all the other stuff that’s in the pipeline, I need to play some serious Bookcase Tetris. It’s a good problem to have.

“Will.”

Riker jumped, feeling slightly flustered. Being startled aboard the vessel he called home was one thing. It was quite another when it was the soft, melodious voice of his Imzadi. Suddenly feeling a renewed pang of guilt as he realised that Deanna Troi could absolutely sense his discomfort, and then another pang of guilt because he knew she could also sense that – this was getting paradoxical – Will turned, straightened up to his full height, tugged on his uniform and innocently enquired “Something I can do for you, Counsellor?”

Troi tilted her head. “Well, we’re both off-duty. I wondered if you wanted to spend some time together, but the computer said you were back down here. Again.” She hesitated, gesturing towards the large archway that Riker had been bracing against. “It was only a few days ago that you and I stood on that very holodeck and watched Admiral Archer–”

“Captain Archer.”

“–Jonathan Archer give the speech that birthed the Federation. The Pegasus incident is behind us, Will. Admiral Pressman is facing charges. He’s probably also facing being shipped out to some…I don’t know, some deserted island somewhere. Why are you still so tense? And also…”

Troi’s gaze drifted down towards Riker’s hand and her brow furrowed. “Is that a… tomato? A burnt tomato?”

Ten thousand lies, bluffs, strategies, excuses… None of them would be enough to faze Counsellor Deanna Troi. Riker knew that well enough by now, and sagged a little. “Look, Deanna… after we got done rooting through the past adventures of Archer’s Enterprise. I got greedy.” He let out a slow breath. “Perhaps I even got a little reckless. So I asked the computer to disable the heuristic protocols and predict our future. To see where we’d all be fifteen years from now. Give or take.”

Troi’s dark eyes widened in surprise. “Will! The heuristic protocols are only supposed to be enabled during tactical emergencies. There’s no reason for you–”

“Captain Picard is going to die.”

He didn’t remember Deanna reaching out, but there she was, her hand clasped tightly over his. “We’re all going to die, Will. And the holodeck isn’t a fortune-teller.”

“No, but…” Riker shook his head. “I was stupid, I went in blind. I could have read the synopsis but I just dove straight back into– well, me, I guess. My life. Yours, too. We were…” He hesitated, but there was no turning back now. “Together, you and I. A family, with a little girl.”

“Will, that’s nothing to be–”

“It used to be two.”

Mercifully, Deanna said nothing. Riker’s sleeve found its way across his face, wiping away a sudden wetness as he continued. “Nepenthe. We moved to this planet because of a virus… and Data was gone, and the Romulans… The Borg… Oh god, Deanna, it all went so wrong.” The words forced themselves out of his heaving chest now as the anger bubbled. “The Captain. Data, for God’s sake! Our family, our friends… They all deserve more! SO MUCH FU–”

Riker practically gagged on the word as it floundered on the tip of his tongue. Angry or not, he was a Starfleet officer. There were some old Earth customs, like cursing, that had had their day, and he’d be damned if he’d allow his fear or fury to rebith them. “They deserved more,” he finished, limply.

Troi’s voice filled Riker’s thoughts as she pulled him close, and though he felt vaguely ridiculous with her tiny figure ungainfully wrapping his own, he allowed himself to be drawn into the embrace. Their touch brought a kind of contact he had all-but-fogotten over the years and he sank down inside himself, allowing Deanna’s mind to wash over him.

I can’t promise we’ll always have good times, Imazadi. I can’t promise that we’ll never be sad. We might even lose hope, sometimes. When those moments come, we shouldn’t cast our net outward in search of answers We should look inside ourselves. We, each and every one of the burning stars of this galaxy. If one of us loses that hope, the others ignite it. That’s our oath. That’s what it means to be part of a family. However long that family gets to be together.

Riker’s eyes were heavy and sore, and tears flowed freely from them as he held Deanna tightly. He knew that she and Worf were… close, now, but in that moment he’d have fought the whole damn Kilngon Empire to feel his future wife – if that future were indeed to be – against him. After a few moments of silent, agonising release, he felt the last of his pain flow away, into the ether. Despite the Dickensian images of Christmas Yet to Come, William T. Riker was himself again.

“Thank you, Deanna.” He said, hoarsely. His throat felt red-raw. “You’re right. Whatever happens, whatever I saw, I won’t let it define who I am. You know what? Despite everything, I actually still like who I am. Who we all are. Nothing’s going to change the people we were yesterday.”

“Then tomorrow can’t be all that bad, now can it?” Deanna pulled herself away from Will. “Well, I have an appointment to get to. See you on the bridge at eighteen-hundred?”

“Mmm,” Riker watched, still queasy as he recovered himself. Hugh… Gulping deeply, he decided that maybe it was best to place a blocker on his holodeck protocols for a while, at least when it came to speculative fiction. Clearly there were still a few kinks to work out. After all, he reasoned, regaining something of his customary swagger as he made his way to the turbolift, it wasn’t like the computer, churning out stories with the dreadful arithmetic of a device seeking to offer entertainment, understood the human adventure.

It didn’t understand it at all.

Blimey, hello you. It’s been a while since I’ve had anything of substance to post here, as I’ve been rather busy with a few new projects. Now, though, the time has come to transform this place from an out-of-the-way blog used I store my assorted ramblings to a showcase for myself, my professional output… and, let’s face it, more assorted ramblings, because video games aren’t going to discuss themselves*.

If you’re new here then welcome – if you’re wondering who I am and what I do then the About and Portfolio pages should be your first port of call, or you can check out the categories menu to find things I’ve written. Either way, enjoy – and watch out for the semi-colons; they’re still wet.

The recent release of Sonic Mania and the way it’s managed to both recreate and reimagine the classic games’ look and feel – with an authenticity that finally satisfies the die-hard fans, no less – has roused players’ curiousity in a way that not even 2011’s Sonic Generations managed to achieve.

Whether they’re eager to rekindle faded memories of a mate’s Megadrive or taking their first interest in a series that’s been supported and scorned with equal passion over the years, something about Sonic Mania‘s heritage – and the confidence with which it celebrates those 26 years – is inciting players to take the rapid little rodent out for a spin. The result, it’s fair to say, has been a fair amount of bafflement from those who, despite a healthy knowledge of gaming genres and retrogaming in general, can’t quite work out what all the fuss is about.

More specifically, these players point out what they perceive to be a paradox at the heart of Sonic‘s gameplay: the game encourages you to go quickly, often wresting control of your character away to accelerate you up to a breakneck pace, only to apparently punish you for enjoying the cheek-juddering velocity by slamming Sonic straight into an obstacle you couldn’t see coming. Moreover, speeding about the place tends to whisk you helplessly past extra lives, power-up shields and even bonus stages – things that would be a definite advantage to a new player in particular.

The question, and it’s certainly a valid one, has been asked repeatedly: “How am I meant to play Sonic games?” As an infernal busybody, it was only a matter of time before I attempted to have a stab at examining why Sonic isn’t like other platformers, why its fans like it, and ultimately trying to provide an answer.

A word of warning: I am now going to invoke Mario. While it should certainly be possible to dissect a game’s design without reference to other works, the plumber and the hedgehog are entangled at a quantum level thanks to a prolonged marketing campaign that hinged on a single tenet: Sonic was better than Mario because Sonic moved faster.

We’ll examine the truth of that statement in a moment, but it’s important to remember that when Sonic debuted in 1991, the notion of “going fast” in video games was something of a novelty. Older consoles often didn’t have the horsepower to provide a convincing sensation of speed – which shouldn’t be confused with actually playing more swiftly, of course. Home console versions of Arkanoid require lightning reactions, but not in a way that makes you go “Wheeeeeee!”

Portraying a convincing sense of speed, however, was a laudable goal because it made your hardware look inherently powerful – Nintendo’s own F-Zero was designed to feel blisteringly fast – and it’s little wonder that Sega chose to capitalise on the difference, mocking Super Mario World‘s supposedly pedestrian pacing by putting it side-by-side with Sonic 1. When you’re sitting down to play, though, how true is it that Sonic is about “going fast”?

If you’re examining the original Sonic the Hedgehog, breaking it down zone by zone, you could answer “hardly ever” and make a serious case. Sonic 1 is a formative beast, and its zones are littered with mechanics designed to halt the hurtling hedgehog in his tracks. Marble Zone, for example, introduces a box that must be laboriously pushed onto a switch, pistons that move at an agonisingly sedate speed and slow rides across sprawling magma lakes. Not only is Labyrinth Zone (unsurprisingly) littered with dead-ends but the majority of it is underwater, making your controls sluggish and forcing you to wait for periodic air bubbles. Generally you’re not battling Sonic’s breakneck speed in this game, you’re learning to manage his momentum.

Even so, Sonic was now the self-appointed “Fastest Thing Alive” and so future installments dutifully played up to that conceit. Sonic was speedier, set-pieces that pinged him helplessly around the world were larger and more elaborate and players found themselves spending more time simply holding a D-pad direction and enjoying the ride. The flow-smashing obstacles, however, remained.

Why? If going fast and pinballing around Sonic’s pretty worlds is fun, why repeatedly dash the player’s good time – and Sonic himself – against a wall of spikes? I think anyone reading this can imagine how quickly they’d tire of a Sonic who could move endlessly without obstacle or opposition as a sort of 2D “running simulator”, but do the obstacles need to be quite THAT cruel? Must hazards be so maliciously placed that it’s almost impossible to react the first time you encounter them?

Here’s where I think Mario has had his belated revenge on Sonic. In Mario titles, and in the vast majority of platformers that learned their craft from Super Mario Bros., taking a hit is a severe penance. For one thing, getting hurt deprives Mario – and thus the player – of abilities that make him feel powerful, allow him to reach hidden bonuses, and in some cases even complete an objective. (Bye-bye, Cape Feather! You’re doing the level over if you want to reach that secret exit.) A Mario game that sucker-punched you as often as Sonic would be an exercise in abject frustration, as evidenced by the Japanese Super Mario Bros. 2 and its outright sadistic level designs.

When you take a hit in Sonic… you drop your rings. (“Oh no,” as Knuckles might say.) They bounce all over the screen but it’s easy to pick a few of them up again. Even if you don’t, you’ll never be more than a ledge or two away from some more rings. If you die, the game is remarkably kind-hearted with mid-level checkpoints, including one placed unfailingly before each zone’s boss. Only in the final act of each game, when there’s nothing left to play towards, will 16-Bit Sonic maroon you in a one-hit-kill scenario. Bottomless pits are still a concern, but mostly in the later stages. By 1990s standards, this is all positively magnanimous.

Sonic is a series that expects you to go too quickly for too long. The rings system is designed to provide you with a nigh-unlimited safety net. There’s nothing to stop you braking after you come out of a tunnel or a booster but the level designers know that you won’t. The joy of speed is too much; like Icarus, you’ll fly too close to the sun and… You get a smack on the wrist. A momentary time-out. Then you grab your rings, drop into a spin dash and hurtle off again.

Stick with this dizzying and unfamiliar pattern of reprimanding, and you’ll find that over time, the game’s not smacking you so much. You’re getting a feel for when the stage might be about to chuck an obstacle in your path – the build-up before the potential pratfall is pretty consistent in the more popular entries – and avoiding that obstacle will often net you power-ups, a bonus stage or a quicker route.

And it’s routes that bring us onto another key difference. It’s extremely unlikely that a new player, one attempting to succeed purely by reflexes, will take the same path through a zone twice in a row. The levels are intricately designed so that a missed platform or errant badnik will send you off the beaten path and to somewhere entirely new. That’s important too, because while Sonic games are comparatively short, they began in an era with no game saves.

The Mario series rewards inquisitive or knowledgeable players with Warp Zones; tools to circumvent the path most trodden and get back to exploring the unknown. Cheats notwithstanding, Sonic knows that you’ll be tearing through Green Hill Zone every time you boot the console. It doesn’t demand that you commit every pit and peril to memory in order to succeed, it’s just confident that the more you play, the more that’ll happen anyway.

Before long, and through no conscious effort or grind, you will be going fast. Dodging the spikes. Hitting the springs. Snagging the extra lives out of palm trees and waggling your finger as another Egg-O-Matic explodes. You’ll feel incredibly skillful, like you’ve started to master the game. In a world where cartridges were precious treats for kids to covet, rent and trade, replayability was absolutely essential. In Mario‘s case, that replayability came from uncovering layer upon layer of secrets. In Sonic‘s case, it came from rolling with the punches, keeping your eyes open and never, NEVER letting Tails steal your zipline, the two-tailed git. As you played, you’d improve, but it never felt like a chore.

Sonic Mania has arrived in an age of disposability. We have more games than ever before and so much vying for our attention. In many ways, the notion of mastery is a faded conceit, the domain of those who squabble over leaderboard placements and tell others to “git gud”. Sonic Mania demands very little to complete, and it’s sadly likely that its generous save system, as with Sonic 3‘s, will mean that something gets lost in translation.

Many of the people who have bought Sonic Mania will play each level once. They won’t dip into Time Attack, seek out the special stages nor play as Knuckles (& Knuckles). They’ll experience something that can feel stubbornly obtuse and out of time, a game that won’t provide an unbroken flow and is often unfair. A game that expects you to come back but wants you to understand that next time, things will be different.

It’s a real shame, but it’s part of Sonic Mania‘s commitment to authenticity; despite perceptions of what Sonic “is”, this love-letter has avoided becoming the shallow roller-coaster that so many of the series’ least-satisfying 3D outings ultimately provided. A shame, then, that its audience may already have stumbled one too many times, shrugged and moved on to the next game — because how else do you deal with the modern-day gaming backlog?

Gotta go fast.

This evening I was changing my bed linen, which involved one of the lifelong battles with which any adult in a temperate climate should be familiar: getting the duvet back inside the duvet cover. It wasn’t my most successful campaign; I’d managed to catch my finger on the door latch and almost break the light in my frenzied attempts to stuff one large, unwieldy piece of fabric into a much lighter piece. This was the instant of my epiphany.

Whoever invented the duvet cover is an idiot, and we are fools for letting them get away with it.

In case you’re the type of person who doesn’t have to change duvet covers – perhaps due to local climate, youth, wealth, vagrancy or mastery over a genie – the issue is this: duvets need to live inside duvet covers for reasons of bedroom aesthetics, avoiding skin irritation while sleeping and (if you’re allergic to dust mites) not waking up with your airways filled with more crap than a UKIP manifesto.

The problem is that only one side the duvet cover actually has an opening – one of the narrow sides, the one kept at the foot of the bed by all right-thinking individuals. This necessitates that you “push” the duvet up into the cover, which is stupid, because fabric doesn’t push well. Fabric bunches, and of course when it does there’s a huge amount of friction against the duvet cover itself which, being lighter, decides to come along for the ride. Having to wrestle with inch after inch of quilting in this way isn’t just stupid, it’s an affront to our innocent comrade-in-arms, physics.

I was stood at the end of the bed, rumpled and furious, when I realised there could be another way. A better way. Once the duvet’s in, you see, you can regain some measure of satisfaction by sealing the bloody thing away with plastic studs, colloquially called poppers (at least when I was growing up) thanks to the satisfying sound when you seal them. Why, I fumed, couldn’t they at least put the poppers on the “side” of the duvet cover rather than the bottom? At least that way you’d be able to reach in with your arms and tug the duvet most of the way in, which is only feasible from the bottom end if your Dad’s Mr. Tickle.

No, hang on… Why couldn’t all of the sides have poppers? If that were so, you could simply:

1. Arrange the bottom portion of the cover on your bed with the poppers facing up.

2. Place the duvet on top like the filling of a snooze sandwich, then

3. Lazily – nay, decadently – lay the rest of the cover on top and pop the two halves together!

Even if you kept the edge closest to your face “popper-free” as a defense against all those nasty allergens, it’d still transform the way we make our beds. And as a bonus, all of the wayward pants and pillowcases that inevitably end up trapped in the duvet cover could be recovered with grin-inducing ease. As a nation, we’d save billions on socks alone.

I want this to happen. I think we, as a species, need this to happen. It’s been a long time since sliced bread, and there’s space for a new Greatest Thing. In fact, if people read this blog and don’t march on Parliament to ensure we can drag our duvets into the twenty-first century, rather than endlessly around the bedroom, I’m going to learn to sew well enough to file the patent myself.

Just as soon as I’ve made the bloody guest bed.

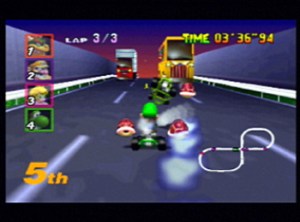

Released just two years after Mario Kart: Double Dash, the shortest gap between entries to date, there was no doubt that Mario Kart DS had a lot riding on its success. The chaotic, weapon-heavy races of the series’ Gamecube outing had alienated some of Nintendo’s audience and core titles were thin on the ground, but with a broad DS consumer base already enticed by titles like Brain Training there was a delicate balance to be maintained if Mario Kart were to maintain its popularity.

Mario Kart DS was to be a straightforward title, one that sought to take advantage of the DS’s improved connectivity and provide a “best-of-breed” entry without anything that might be perceived as extraneous gimmickry. Racers were once again driving solo, slipstreaming returned and was given a visual makeover, and the density of weapons fire was greatly reduced. Possibly the greatest demonstration of the game’s rebalancing is the remade Double Dash circuit Mushroom Bridge; all but one of that track’s many shortcuts and its speed boosts have been stripped away, leaving an experience that’s almost sedate by comparison.

For some, it was a balance that had shifted too far. It was easier than ever to pull off drift boosts and thanks to the width of the new circuits, savvy players soon discovered that they could “snake” along straights, repeatedly drifting this way and that to earn boost after boost. As the technique spread across the internet, online matches became a stratified tussle with elite players cramming as many drifts into a single corner as possible, and bemused novices who couldn’t or wouldn’t follow suit being left inexorably behind.

With no number of blue shells able to disguise the frustration at opponents who were just plain faster than you, there were more than a few cross words to be had. Many of these were directed at Nintendo themselves, with demands to “patch the game” and eliminate snaking (and just as many demands to maintain the status quo) showing just how intertwined the relationship between developers and players had become in an online age. While the game was never updated – the DS’s online flexibility was far removed from the PCs and consoles of its time – it’s fair to say that the majority of Mario Kart DS‘s 20 million-strong audience were oblivious to the hardcore’s discontent.

Nor would snaking spell guaranteed success in single-player races, as the preferred racing order and rubberbanding returned once more. Mario Kart DS‘s single player was a thoroughly challenging affair after Double Dash, with blue shells and lightning bolts causing trouble for players even on 50cc races. While there were few unlockables this time around – the number of karts had been reduced and were now driver-specific – there were still secret characters for completionists to discover. More intriguing were the large number of single-player missions; familiar territory to anyone who’d experienced arcade racers like the Project Gotham Racing series. Players were tasked with bite-size challenges like racing through gates or driving backwards before being ranked on their performance and ultimately coming up against Bowser’s minions in boss battles. Despite having a significant amount of content, these missions were entirely optional and offered no larger reward – had they been presented in combination with full races, they could have provided the series’ first true solo campaign.

Not that solitary players had to content themselves with racing alone; most of the barriers to entry that had thwarted Super Circuit had been removed by the DS’s hardware; a way to exchange friend codes was all that was needed to battle opponents globally. The single-cart “download play” feature returned, too, letting players effectively demo the game to their DS-owning friends. With Nintendo’s online infrastructure in its infancy, there were a number of sacrifices – items couldn’t be dragged or spilled and twelve of the game’s courses simply weren’t selectable – but there was a definite joy in being able to finally test your Mario Kart metal against distant friends or forum rivals alike.

As had come to be expected, the title displayed a high level of visual and audio polish, with polygons wisely spent on the characters rather than the scenery. With no DS Mario offering as yet, the game chose Super Mario Bros. 3 as its motif – a decision that delighted older players and allowed for many tongue-in-cheek references, like the Angry Sun disgorging fire snakes into the twisting Desert Hills course. While several of the tracks were unambitious or rehashes of what had come before (Wario and Waluigi’s circuits in particular borrowed heavily from Double Dash) there were more hits than misses – the sharp angles of Delfino Square and Airship Fortress would go on to become fan favourites.

Every Retro Grand Prix, meanwhile, was arranged nearly into an entry from each generation, with some faring better than others. While the Gamecube courses transferred remarkably well considering the DS’s reduced horsepower, the SNES tracks had been radically scaled up to provide a meaty race within a three-lap structure and lost much of their challenge and distinctiveness as a result. With the entire back-catalogue as yet unplundered, some of the returnees seemed questionable – the Shell Cup was mostly composed of starter courses while unloved entries like the N64’s Banshee Boardwalk padded out the later cups. Even so, with retro tracks now standard fare for any Mario Kart, it’s important to remember how impressive the remastering seemed at the time.

Taken as a whole, Mario Kart DS was an impressive if risk-averse entry, and received the critical acclaim it deserved, striking a better balance of racing and items than Double Dash and giving the DS a flagship title for its core audience. To assess the game’s legacy, one need look no further than its successors – it set the template for Mario Karts to come, with everything from its mixture of new and retro courses to the layout of its HUD being reprised in future titles. Even without analogue steering, anyone who returns to the title today will acclimatise easily, slipping back into a well-worn pair of driving gloves. With the closure of Nintendo’s WFC service it’s the first Mario Kart to be lost, at least in part, to time, but so much of its spirit survives in other titles it’s hard to feel too much loss. Mario Kart DS is dead – long live Mario Kart.

(Images taken from Nintendo UK )

Seven years is a long time in gaming. Entire consoles rise and fall, companies and individuals alike can go from rags to riches — but most significantly, games themselves undergo a continual transformation moulded by the experience of their creators and the expectations of their audience. In Mario Kart‘s case an entire genre had been born around its core gameplay. Kart racers had become as ubiquitous as 3D platformers or 2D fighters before them, and while most had been slapdash efforts based around licenced property, some titles had refined or innovated the genre while Nintendo had been slumbering. For Mario Kart to retain its best-of-breed status, it needed a headline feature – something to help it stand above and beyond its many imitators.

Equally important, from Nintendo’s perspective, was that the series capitalise on its historically broad appeal. The team was tasked with creating a new entry that could be enjoyed by veteran players without alienating those who were new to the series or to gaming in general. Simplicity was the watchword; features like Game Boy Advance connectivity were mooted and then dropped as the team sought for that elusive, iconic innovation that would attract new and old fans alike. The result was Mario Kart: Double Dash!!, the two exclamation marks the first indication of how unashamedly brassy and cacophonous this entry would be (and discarded for the rest of this piece).

Each kart in Double Dash would hold two racers, mixed and matched from the roster at the player’s whim – an arresting visual hook from which the rest of the game’s unique mechanics fell naturally. Karts now had unique properties of their own, with the choice of characters determining which class of karts were available to each player. Bowser was never going to squeeze into Baby Mario’s buggy, but it didn’t mean he was bereft of the choices offered to smaller players. More significantly, each player now had a signature “special weapon” that might appear from the item roulette. High powered and chaotic, smart pairings of characters could ensure that these weapons had devastating consequences when unleashed in pairs.

The ultimate exploration of the pairing mechanic allowed two human players to share a single kart, switching between the “pilot” and “gunner” positions respectively. While this mode offered some intriguingly social opportunities, including the ability to steal other drivers’ held items with a precision side-swipe and the titular “Double Dash” boost, karting by consensus was much slower and wasn’t quite enough to occupy each player’s attention during the event. Ultimately, the most fun was still to be had in races where everyone had a kart of their own, particularly if you could avail yourself of the eight-player LAN feature (a mode that required Super Circuit levels of peripherals and forethought to set up).

With each kart now in need of a passenger, the character roster was expanded for the first time since the series’ debut over a decade before. Even more characters could be accessed thanks to the game’s many unlockables – a first for the franchise and an incentive for seasoned players to take part in the easier cups – bringing the total up to 20. Petey Piranha and King Boo were wildcards who might receive any of the other characters’ special weapons, while Toad and Toadette fleshed out the understaffed lightweight class. Solo players had another reason to celebrate; the AI rubberbanding had been greatly reduced compared to other entries in the series, and a doubled weapon inventory made it easier to reclaim first place in the event of a particularly harsh blue shell.

Weapons were to be the great leveler of Double Dash; the key to its accessibility and the bane of those players who placed greater emphasis on racing lines than marksmanship. The game’s tempo led to earning and discarding items almost immediately and the secondary mechanics all fed into that – players could no longer drag items, shells no longer orbited their owner and taking a hit (which would happen on a regular basis) meant your held items would go tumbling onto the tarmac ready to be picked up by another player. Even boosting into an opponent would be enough to empty their pockets. When giant Bowser shells, rampaging Chain Chomps and item-nabbing shields were unleashed as special weapons the result was rough and tumble; a free-for-all where first place was often decided on the final bend and no-one lagged behind for long.

Players can use mushrooms to boost through the flooded sections of Peach Beach, avoiding murderous Caterquacks.

The track design further encouraged this riotous behaviour; most of Double Dash‘s courses were heavily interwoven, briefly splitting players apart before bringing them back together (occasionally in a head-on showdown). There were no coins to collect, but the prized double item boxes were used as rewards for discovering alternate routes or consolation prizes for being sent the long way around. Bona fide shortcuts abounded, but more frequently relied on the ever-present items to navigate successfully. The tracks themselves, while less experimental than Mario Kart 64‘s first foray into 3D, were a varied assortment ranging from the downhill off-roading of DK’s Jungle Mountain to Waluigi Stadium, a treacherous metal walkway as warped as Rainbow Road itself. The shift away from racing finesse was never more apparent than at Baby Park, a diminutive oval that could easily have been mistaken for a battle mode arena.

Nintendo had succeeded in levelling the playing field, but while some delighted in the rambunctious, no-consequence appeal of Double Dash‘s multiplayer, there were those – gamers and critics alike – who lamented that skill and mastery counted for so little this time around. Edge Magazine‘s infamously scathing review declared the title to be a “party game” instead of a racer – an opinion that could only have been compounded by the simplicity of the single-player experience compared to the attention lavished on the co-operative and battle modes. Ten years later and with no weight of expectation, attitudes towards Double Dash have softened, but the irony remains: Nintendo’s studious attempt to make a Mario Kart that appealed to everyone ultimately resulted in one of its most divisive creations to date.

( Images taken from www.nintendo.co.uk )

Overshadowed by its TV-hogging siblings, Mario Kart: Super Circuit is often relegated to a footnote in Mario Kart lore. Developed by second-party stalwart Intelligent Systems (who’d recently provided Nintendo with the charming Paper Mario) and released early in the Game Boy Advance’s life cycle, the title never managed to grab the attention that other, more experimental entries in the series would attract.

A shame, but perhaps not entirely unexpected – at first glance Super Circuit is Mario Kart by numbers; a fusion of technical implementation and artistic direction that borrowed from Super Mario Kart and Mario Kart 64 in equal measure. While Nintendo had vehemently disputed comparison of the GBA to a portable Super Nintendo, a title that so heavily aped Super Mario Kart (going so far as to include all of its courses) only aided the perception that Nintendo were dusting off (or in the case of Super Mario Advance, chopping up) their SNES catalogue and charging players £35 for a lick of paint and some grating voice samples.

The first game in the series to visibly show a character’s stats, players would earn higher ranks for completing courses as “poor” characters.

Nor was Super Circuit afforded the solitude that had been granted to its predecessors. The GBA launched with several racing games to compete against, having been beaten to launch by Konami Krazy Racers, Super Circuit had to battle against titles like Nintendo’s own F-Zero: Maximum Velocity for hearts and wallets alike. While Goemon and the rest of Konami’s creations weren’t as recognisable as the likes of Mario and Bowser, these titles added to a sea of SNES-like racers and made it harder for Super Circuit to distinguish itself.

The game’s steering mechanics closely aped that of Super Mario Kart, with its flat courses featuring plenty of hairpin turns and narrow pathways to negotiate – even on 50cc, the races felt pacier than Mario Kart 64‘s sprawling experiments. Drift boosting was gone, though players could get a secondary “boost-start” after being rescued by Lakitu. Coins had returned, this time placed in neat clusters rather than the sprawling, corner-hugging arrangements of the past.

While Mario Kart entries tend to take visual inspiration from the most recent entry in the core Mario series, there had been none since Mario Kart 64 – that game fashioned character sprites out of high-fidelity 3D renders, and Super Circuit did the same, the roster remaining unchanged this time around. Mario’s arsenal was familiar, too – most items (and the ability to drag them) were ported across wholesale. The golden mushroom was notably absent, as the normal variant once again gave a burst of speed (as in Super Mario Kart) rather than maintaining top speed over rough terrain.

Super Circuit has just four images on Nintendo’s web page, most with a conspicuously drab colour palette.

If the mechanics and weaponry were overly familiar, however, players could at least enjoy exploring a plethora of new environments, many of which have yet to return to the series. Accompanying the traditional tarmac circuits and frozen lakes were such memorable entries as Cheese Land (obliquely set on the moon), the celebration-themed Ribbon Road, aquatic Ghost Houses and deserts with both Egyptian and Wild West motifs.

Several of these courses changed dynamically as the race progressed, with the sun setting behind distant mountains and periodic volcanic eruptions. While these events never fundamentally altered the player’s route, few Mario Kart tracks since then have undergone such striking visual changes mid-race. Yet despite this variety, it seemed as though Bowser had been bribing someone at Intelligent Systems – counting the tracks from Super Mario Kart, the game features a staggering seven Bowser Castles in all.

Not all of the game’s visuals were praiseworthy. While the backgrounds featured several layers of parallax scrolling, they moved far too little to present a convincing skybox instead became disconnected and distracting. Additionally, no attempt had been made to reduce the many HUD elements from Mario Kart 64 and, in fact, an arcade-style “turn warning” had been introduced, cluttering an already tiny screen and making shortcuts at the periphery of the track hard to spot.

The Lightning Cup starts out, appropriately enough, on a rain-soaked circuit with puddles that spin you out on contact.

Like many GBA games, Super Circuit used a bold, sometimes gaudy colour palette to provide contrast on the Advance’s dull and unlit screen. Unfortunately, this led to some ugly screenshots for the game’s release – a perception not helped by the introduction of the Game Boy Player, a Gamecube peripheral that often brought games to the TV in a less than flattering light. At least the soundtrack remained varied and rich in texture despite the GBA’s limited audio capabilities.

Yet if Super Circuit could claim real harm from the GBA’s oft-revised hardware, it was in the effort necessary to play multiplayer matches. Linking together multiple handhelds required a complicated web of (rather pricey) cables that left people jostling for light and comfort. While the game commendably featured single-cart multiplayer, restricting very little other than the character roster, the full game required a significant amount of setup for an experience that wasn’t significantly improved over what had come before. This was one Mario Kart that, more than ever, needed to survive on its single-player merits.

While the solo experience had ironed out some of Mario Kart 64’s frustrations – rubberbanding was still present, but less intrusively apparent – the decision to lock away the game’s content proved an unpopular stumbling block. While Super Circuit boasted forty tracks in total, players had to complete every single cup at least twice over (and with enough coins) to unlock half of them. For those looking for a kart ride down memory lane, it was an annoyance to say the least… and the execution of the coveted retro courses was haphazard, missing their original graphics, coin patterns and many of the obstacles.

With the Gamecube’s arrival so soon after Super Circuit‘s debut, attention soon shifted to the promise of a “next-gen” Mario Kart; a title with 3D, rumble and internet play – Nintendo had already shown a brief E3 teaser. With little innovation on display, Super Circuit was a solid but unremarkable entry doomed to second-fiddle status by an unfortunate combination of Game Boy logistics and Nintendo’s own hype machine. Even today, it’s a curio: the plaything of 3DS early adopters, bereft of its multiplayer and left to languish in the shadows. And yet the notion of retro courses endures – perhaps Super Circuit‘s creators can take heart in the possibility that their best tracks, many yet to be revisited, may one day be appreciated in Mario Karts to come.

(Images taken from http://www.nintendo.co.uk )

Delaying Mario Kart 64 couldn’t have been an easy decision. Much had been made of the Nintendo 64’s four controller ports, one-upping (or rather, two-upping) the upstart Playstation and ensuring that games like Bomberman and Worms could be played the way nature intended. By sacrificing team members to the timely completion of Super Mario 64, Nintendo were leaving themselves without a title that supported multiplayer of any kind, least of all their promised utopia of four friends battling for supremacy.

Launching in Japan in late 1996, it became apparent that the game – which had once been obliquely dubbed “Super Mario Kart R” – may have lost its SNES prefix, but the gameplay was an evolution, rather than a reinvention, of a title that had overcome critical indifference and become an enduring classic. Nips and tucks had been made: coins were the most notable casualty, though few lamented their passing. Additionally, the game’s four-tiered driver stats had been reduced to three, inadvertently ensuring that arguments over who got to play as Toad would last for the rest of the console generation.

Mario Kart 64’s title screen would change as players completed objectives, but most content was available to dive into right away.

It was to be two under-sold mechanics that would go onto define not just the Mario Kart franchise but also shape the wealth of copycat karting games to come. In this new edition, pushing a power-slide to the very brink of catastrophe and then slamming the analogue stick in the other direction would see your smoke trails turn from white to orange, netting you a handy burst of speed when you exited the turn.

While the intricacies of drift-boosting would change in the games to come, here was an implementation that allowed skillful players to boost several times around even the gentlest of bends, opening up a whole new level of depth. Slipstreaming, while curiously redundant in a game so heavily weighted towards dragging your items as shields, was also introduced in Mario Kart 64 and has made a number of reappearances (to much better effect) since then.

While there were relatively few new items considering the imagination that the Mario series has always been famous for, the headliner of Mario Kart 64‘s arsenal became one of its most notorious. The blue shell would zoom around the circuit at high speed, blatting aside anyone unlucky enough to get in its way before seeking out the first-place player and exploding in a ball of polygonal fire. Gifted surprisingly rarely considering the reputation they’ve come to earn, the blue shell was either a canny way of levelling the playing field between players of different skills, or a punishment for doing well and the downfall of Western civilisation – a view that normally depended on whether you’d just been on the receiving end.

“Fake” Item Blocks made their first appearance, and were far harder to distinguish than in future installments.

The blue shell was also one of the few weapons that could push past the stockpile of goodies players built up as they raced. Not only could single items be tugged along behind your kart to absorb the impact of an attack, but shells now came in orbiting packs of three, meaning that just brushing your opponent could be enough to send them tumbling. Seeing players armed with six red shells wasn’t uncommon, a frustrating arsenal that would later become the special weapon of just two characters in Mario Kart: Double Dash. Weapons were retained during collisions, which led to protracted exchanges of fire between human players and should have been enough to see off the CPU opposition… were it not for one of Mario Kart 64‘s most divisive decisions.

While the running order was no longer determined by the player’s own character, certain drivers would once again be picked out to act as the player’s rivals. Unlike Super Mario Kart, however, these opponents were artificially and continually placed to snap at the player’s heels – a mechanic usually referred to as “rubberbanding”. These rivals would buzz around your character so closely that they’d inevitably crash into, and deduct from, your defensive items over and over again, spinning out of sight only to return unscathed a moment later at speeds any human would find impossible.

While rubberbanding in racing games was not uncommon – some claimed it provided an action-packed race regardless of your skill level – the approach had become increasingly criticised as control systems gained the fidelity to emulate the skill of real driving. Even on 50cc settings, being jostled and harassed often diminished any sense that the player was improving, as well as making attacks seem powerless and feats of skill unimportant. It was also a decision that could wreak havoc in a two-player Grand Prix; a trailing human player would get caught up in the rabble trying to fight past particularly aggressive AI for a stab at first place. Sadly, it would be a dilemma Nintendo would continue to struggle with in years to come.

In a series renowned for its visual polish and art direction, Mario Kart 64 contained a number of interesting quirks and oddities, some of which showed Nintendo’s experimental design process at work. For one, the game had three completely different HUDs that the player could switch between at any time; the (now standard) Player List & Map combo, an all-but-useless speedometer and an abstract representation of each player’s relative position. Additionally, player actions were overlaid with bizarre onomatopoeia, with “Boing!”, “WHIRRR” and (a personal favourite) “Poomp!” accompanying hops and impacts.

Coming so soon after Mario 64, seeing Peach’s Castle tucked away as an afterthought was an impressive display of horsepower.

Other unusual features included the ability to dynamically adjust the music volume, a feature mapped awkwardly to the L button and therefore barely accessible during normal play unless the player owned a friendly octopus. Equally redundant was a single control meant to move the camera further back from your kart – but since the player effectively was the camera, all this did was rapidly (and nauseatingly) fiddle with the field of view. The rear-view mirror, sadly, did not make a reappearance.

Looking back, it’s clear that Nintendo were determined to use every last polygon to explore a wide variety of terrain for their track designs. While the environments themselves stuck to familiar motifs, the diversity of their layout and how they made use of “true” 3D was impressive. Unfortunately, with so many ideas on display, it was perhaps inevitable that some would fare better than others. Highlights included the bumpy, Motocross-inspired terrain of Wario Stadium and the almost SNES-flattened ground and right-angled turns of Bowser’s Castle, while Yoshi Valley (a tangled maze of intersecting routes) simply didn’t work. One route was demonstrably fastest, so experienced players would sail onto the second half of the course (an inexplicably barren meadow) leaving newcomers confounded and annoyed.

Equally infuriating were the courses that set you back a full minute for taking a hit mid-jump, or ones that delighted in simply blocking the way ahead with a train or giant egg. It culminated with DK’s Jungle Parkway, a track which sped its racers across a huge gap only to leave them facing in the wrong direction, necessitating an awkward about-turn from each and every player. The game’s soundtrack was consistently enjoyable, at least, with first-time composer Kenta Nagata contributing several themes that would go on to become series staples.

Much like its forebearer, Mario Kart 64 relied on its multiplayer to make the most of what were, at its core, still inherently fun and compelling gameplay mechanics. The N64’s first four-player game required a few technical sacrifices – there was no music, and the lack of a frame rate lock meant that some tracks ran at almost twice the normal speed – but the battle mode in particular benefitted greatly from a 3D overhaul. The most successful courses were those that were practically shooter-like in their construction, allowing for multi-level assaults and quick escapes.

Toad’s Turnpike made good use of 3D, squeezing players between looming vehicles that could change lanes on a whim and send you tumbling.

While battle mode remained a highlight, it didn’t have the lasting impact of its ancestor. Super Mario Kart remained something of an oddity within the SNES library, which meant that battle mode did too, but the youthful N64 would soon offer many ways to step out of the go-kart and hunt your friends down in first-person, all of which challenged Mario Kart for the multiplayer throne. In years to come, the console would also see more technically accomplished racing games attempt to topple the series – usually substituting in hot property like the newly born South Park in their efforts to do so.

Yet despite the suddenly crowded playing field, Mario Kart 64 was once again a sales success – and this time, the critics were on-board. While the game received a solid string of 8s and 9s from the press, it was noted that compared to the N64’s launch titles – games Mario Kart 64 had once been planned to sit alongside – there was little evidence of radical thinking. While Super Mario 64 had just redefined the platformer and Pilotwings 64 had taken full advantage of all that 3D space could offer, Mario Kart 64 had done little more than (as one critic put it) “soup-up” the original without addressing some of its fundamental problems.

Yet for all its faults, the game laid the groundwork for modern Mario Kart titles – not for nothing did other companies chase its popularity and charm well into the dying days of the N64. Rough and ready in parts, gloriously future-thinking in others and sometimes just plain baffling, Mario Kart 64 did a lot with a little – for better or worse – and set the series on a course that would remain largely unaltered for the next eighteen years.

(Images taken from http://nintendo.co.uk)

You must be logged in to post a comment.